A geyser of methane and gas sprays out of the ground near a Shell drilling site in Tioga County. StateImpact Pennsylvania obtained this picture from a nearby landowner.

A geyser of methane and gas sprays out of the ground near a Shell drilling site in Tioga County. StateImpact Pennsylvania obtained this picture from a nearby landowner.

A geyser of methane and gas sprays out of the ground near a Shell drilling site in Tioga County. StateImpact Pennsylvania obtained this picture from a nearby landowner.

A geyser of methane and gas sprays out of the ground near a Shell drilling site in Tioga County. StateImpact Pennsylvania obtained this picture from a nearby landowner.” credit=”

In February 1932, the United States was in the midst of the Great Depression. Franklin Roosevelt was plotting a run for the White House. And in Union Township, Tioga County, the Morris Run Coal company had just finished drilling a gas well on a farm owned by Mr. W.J. Butters.

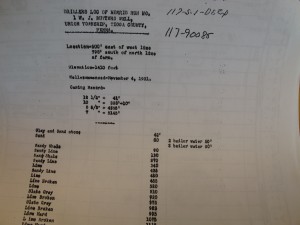

The Butters well was 5,385 feet deep, and lined with four layers of metal casing. Morris Run Coal had a bit of trouble drilling it, though. Two different times, according to the company’s drilling log, workers hit pockets of gas that “blew tools up [the well’s] hole.”

Eighty years and four months later, the Butters well was tied to another incident — even though it had been inactive for generations. It played a key role in a methane gas leak that led to a 30-foot geyser of gas and water spraying out of the ground for more than a week.

The geyser wasn’t the only way the methane leak manifested itself. At the Ralston Hunting Club, a water well inside a cabin overflowed, flooding the building. Methane bubbled out from a nearby creek, as well. Shell asked the handful of nearby landowners to temporarily evacuate their homes while the company worked with well control specialists, a fire department and state environmental regulators to bring the leak under control.

[module align=”right” width=”half” type=”aside”]

Part 1: Why abandoned wells are a problem

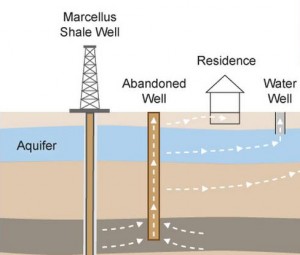

Infographic: How abandoned wells can contribute to methane migration

Part 2: How many wells dot Pennsylvania, and why aren’t we plugging more of them?

Map: Known abandoned wells in Pennsylvania

Part 3: How to track down an abandoned well

Part 4: States don’t do much to regulate drilling near abandoned wells

[/module]

Methane is an odorless, colorless gas that exists naturally below the surface. It isn’t poisonous, but it’s dangerous. When enough methane gathers in an enclosed space — a basement or a water well, for instance — it can trigger an explosion.

The gas didn’t come from the Butters well, nor did it originate from the Marcellus Shale formation that a nearby Shell well had recently tapped into. What most likely happened to cause the geyser in June, Shell and state regulators say, was something of a chain reaction. As Shell was drilling and then hydraulically fracturing its nearby well, the activity displaced shallow pockets of natural gas — possibly some of the same pockets the Morris Run Coal company ran into in 1932. The gas disturbed by Shell’s drilling moved underground until it found its way to the Butters well, and then shot up to the surface.

Companies have been extracting oil and gas from Pennsylvania’s subsurface since 1859, when Edwin Drake drilled the world’s first commercial oil well. Over that 150-year timespan, as many as 300,000 wells have been drilled, an unknown number of them left behind as hidden holes in the ground. Nobody knows how many because most of those wells were drilled long before Pennsylvania required permits, record-keeping or any kind of regulation.

It’s rare for a modern drilling operation to intersect — the technical term is “communicate” — with an abandoned well. But incidents like Shell’s Tioga County geyser are a reminder of the dangers these many unplotted holes in the ground can cause when Marcellus or Utica Shale wells are drilled nearby. And while state regulators are considering requiring energy companies to survey abandoned wells within a 1,000-foot radius of new drilling operations, the location of nearby wells is currently missing from the permitting process.

That’s the case in nearly every state where natural gas drillers are setting up hydraulic fracturing operations in regions with long drilling histories. Regulators don’t require drillers to search for abandoned wells and plug them because, the thinking goes, this is something drillers are doing anyway.

All week, StateImpact Pennsylvania will explore the issue of Pennsylvania’s abandoned oil and gas wells. We’ll explain how shale drilling and fracking operations can push natural gas through these decades-old conduits, how difficult it is to locate and plug the hundreds of thousands of wells, and what, if any, legal obligations shale drillers are under to find and fill them.

Fred Baldassare worked at Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection for 25 years. He spent more than half his career investigating cases of methane migration, where gas from wells, coal mines, landfills or other sources broke loose and made its way to the surface.

Baldassare investigated more than 200 different episodes. Only a handful of them, he says — perhaps five or six — involved an active drilling site communicating with an abandoned oil or gas well. But when the new and old operations did intersect, Baldassare says, the results were often “dramatic.”

Click on the image to view an infographic explaining how methane can make its way to the surface through an abandoned well” credit=”

When energy companies drill down to the Marcellus Shale, deep below the surface, their wells pass through several smaller, shallow gas formations. Drillers go to great lengths to seal off their gas wells, and Pennsylvania regulations require companies to bond their multiple layers of steel casing with top-grade cement. Shell’s Guindon well, located a few thousand feet from the old Butters well, was lined with more than 1,200 sacks of cement, along with four layers of casing ranging from 13 3/8 inches to 4 1/2 inches in diameter.

Most of the time, this casing prevents the shallow gas from moving to the surface. (That’s not always the case – just see StateImpact Pennsylvania’s reporting on a methane leak in Bradford County.)

But if an old, unplugged gas well has been drilled into the same formation already, the new activity can displace pockets of gas, through pressure changes and physical interaction. Baldasarre explains, “that gas can move to the old well, because [the well] represents a low pressure zone and a natural migration highway.

“Gas always wants to go from high pressure to low pressure,” Baldassare continues. “That old well represents a low-pressure zone. Much like water wants to move downhill, gas wants to move to low-pressure zones.” The lowest pressure is near the surface, so once the gas reaches an old well, it will shoot straight up.

And a new well doesn’t need to be present to trigger this migration. Gas can migrate to the surface through these pathways on its own. The state has investigated dozens of cases where unknown wells have led to gas pooling in basements, water wells, or other locations.

Depending on how old the abandoned well is, the casing can be leaky, rotten, or nonexistent. Methane can easily move into natural faults and cracks, following a path toward the surface that can travel through aquifers. That’s likely how gas ended up bubbling into a creek, out of a water well and up into the 30-foot geyser in Union Township.

The damage caused by Shell’s methane leak was relatively minimal, due largely to the fact the gas bubbled to the surface in a sparsely populated, extremely rural area. That wasn’t the case in Dayton, Armstrong County, when a 2008 gas leak led to the evacuation of an elementary school and two houses.

Then, an active, vertical gas rig — not a shale operation — hit a pocket of gas linked to an undocumented abandoned well. The displaced gas moved quickly, racing straight to the surface. It shot straight through 90 feet of gravel, dirt and other fill material, pushing the material to the surface when it spewed out of the ground. “There was a small community literally a few hundred yards away at most,” recalls Baldassare. “The gas was moving toward that community.”

Department of Environmental Protection officials worked with the gas operator to vent off nearby wells in order to lower underground gas pressure. They also installed vents on the homes, to keep methane from gathering in a concentrated place. The efforts brought the well under control, but just barely. “[The gas] got close — eight feet [from one of the houses],” says Baldassare. “Everyone worked together to avoid catastrophe.”

The best way to ensure an abandoned well won’t create a gas leak is to make sure it’s plugged. When wells are cemented shut, they’re much less likely to create a methane pathway to the surface. The cement seals off the conduit to the surface, keeping methane below the ground.

In Union Township, Shell knew about the old Butters well before it began drilling nearby. “As part of our well location screening process, we did map that abandoned well, which we understood had been properly plugged and abandoned,” Shell spokeswoman Kelly op de Weegh tells StateImpact Pennsylvania. “It was determined, due to that, that the old well would not pose any additional risk.”

Scott Detrow / StateImpact Pennsylvania

The Butters well’s drilling log

The Butters well is marked on Shell maps that StateImpact Pennsylvania obtained through a Right-To-Know Request filed with the Department of Environmental Protection. (We asked for all DEP emails and accompanying attachments related to the Shell Tioga spill.)

The presence of the Butters well is better documented than most abandoned wells. The Department had an old drilling log on file, which StateImpact Pennsylvania also received in its open records request.

But even knowing that the old Butters well was there was not enough to stop what happened in June. In the days after the methane geyser erupted, DEP staffers emailed to Shell all the information they could find about nearby abandoned wells. There were three files on record.

Two were for wells drilled after Pennsylvania standardized its oil and gas laws in 1984. Those records included detailed reports on when the wells were initially drilled, how deep they went, and certificates showing that the wells had been plugged according to state standards.

The third was for the Butters well. It was easy to see that Morris Run Coal had drilled the well back in 1932. But there was no information at all about if, or when, the company plugged it once the well had played out and Morris Run Coal had moved on.

Other parts of the Perilous Pathways series:

Part 1: Why abandoned wells are a problem

Infographic: How abandoned wells can contribute to methane migration

Part 2: How many wells dot Pennsylvania, and why aren’t we plugging more of them?

Map: Known abandoned wells in Pennsylvania

Part 3: How to track down an abandoned well

Part 4: States don’t do much to regulate drilling near abandoned wells

StateImpact Pennsylvania is a collaboration among WITF, WHYY, and the Allegheny Front. Reporters Reid Frazier, Rachel McDevitt and Susan Phillips cover the commonwealth’s energy economy. Read their reports on this site, and hear them on public radio stations across Pennsylvania.

(listed by story count)

StateImpact Pennsylvania is a collaboration among WITF, WHYY, and the Allegheny Front. Reporters Reid Frazier, Rachel McDevitt and Susan Phillips cover the commonwealth’s energy economy. Read their reports on this site, and hear them on public radio stations across Pennsylvania.

Climate Solutions, a collaboration of news organizations, educational institutions and a theater company, uses engagement, education and storytelling to help central Pennsylvanians toward climate change literacy, resilience and adaptation. Our work will amplify how people are finding solutions to the challenges presented by a warming world.