Burning Questions: What’s What, When It Comes To Water?

-

Scott Detrow

This week, StateImpact is answering reader-submitted burning questions about natural gas drilling. On Monday, we tackled water testing. Yesterday, we took a look at an issue that popped up after August’s Virginia earthquake: whether or not fracking can lead to seismic disturbances.

Today’s topic: water. We received several questions about water: how much is used in hydraulic fracturing, where drillers get their water from, and what they do with it after well completion.

Water Withdrawal

The average Marcellus Shale well uses about 4 million gallons of water a day, during hydraulic fracturing. Most drillers obtain their water from two sources: nearby municipal water supplies, or rivers and streams. For the water they withdraw from public systems, drillers simply enter into agreements with nearby townships. You regularly see water trucks hooked up to fire hydrants in drilling communities.

There’s much more regulation involved when water is taken from a stream or river. Three different agencies regulate withdrawal: the Susquehanna and Delaware River Basin Commissions oversee the process in their respective geographic areas. In the western half of the state, the Department of Environmental Protection dictates where drillers withdraw water, and how much they can collect each day.

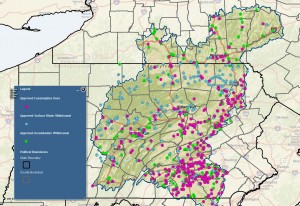

SRBC website

Approved water withdrawal and consumptive use locations, within the Susquehanna River Basin

When the Susquehanna River Basin Commission is involved, drillers need to obtain two separate permits. The first, which gives them the right to withdraw water from a river or stream, takes six to nine months to process. The driller proposes a withdrawal location to the SRBC, who then examines historic water levels and other factors along the tributary in question. “We’re interested in average daily flow,” explained Paula Ballaron, the SRBC’s manager of policy implementation and outreach. “We can look at median monthly flows. That gives us an idea of how much water is typically located [there], and based on that, what might be available for the site.” The SRBC checks out whether or not water is being withdrawn up and downstream from the location in question, and also takes wildlife into consideration. “Like anything else, choosing is about location, location, location,” said Ballaron. There are some optimal places where you get large quantities every day.” And along smaller streams, the SRBC will impose stricter limits.

(Click here to see an interactive map of the SRBC’s approved water withdrawal locations.)

The SRBC treats drilling companies differently than other industries withdrawing water. In any other industry, a company can withdraw up to 100 thousand gallons per day, without a permit. Drillers need the SRBC’s approval from gallon 1, and also pay a steep fee. A driller withdrawing 500 to 1 million gallons a day will pay more than $12,000, plus a $1,000 annual renewal fee. The cost increases to more than $15,000, if the company is taking a million gallons or more each day.

The second SRBC permit covers fracking itself. It’s for “consumptive use,” because fracking water won’t go back into the Susquehanna and its tributaries. This permit is issued on a drilling pad-by drilling pad basis. It’s typically issued within thirty days, but still costs drillers, to a tune of $10,000.

From Water To Fracking Fluid

So the drillers get their permits. What happens next?

They start withdrawing water. Experts at Range Resources — which primarily operates outside the SRBC’s area, in southwestern Pennsylvania – say they try to keep their water sources as close to a well pad as possible, since it costs a lot of money – about $1 per barrel per hour – to transport the liquid.

Range has about 25 central water impoundments in the southwest, in case dry spells trigger moratoriums on water withdrawals, which happened this summer in the SRBC’ jurisdiction. These central hubs can store up to 15 million gallons of water at a time.

When fracking’s taking place, a well will pump about 4 million gallons of water into the ground each day. (SRBC officials say only 10 percent of that liquid will return to the surface later on.) All told, the commission estimates drillers are using about 30 million gallons of water each day, across Pennsylvania.

Drillers, who have gotten a bad rap for their water usage, are quick to put that figure in comparison. “4 million gallons per well sounds like a lot,” said Range Resources’ Matt Pitzarella, “but even if we tripled our expected usage, we’d [still use] less than one half of one percent of the state’s [water consumption.] We would be less than golf courses.”

“We could frack 100,000 wells,” Pitzarella continued, “and use less than a third of one percent of the water that’s in Lake Erie alone.”

After the well has been fracked, chemical-laden water begins to “flow back” to the surface. Pitzarella

said more and more, Range Resources takes that fracking fluid, treats it, and re-uses it during the next frack job. “It reduces consumptive use,” he said, but also “saves us money. We’re not paying for as much trucking and hauling.” Pitzarella said studies have shown recycled fluid will yield just as much natural gas as fresh water.

There’s still waste to dispose of, though. Until this spring, drillers could deliver their fluid to wastewater treatment sites along rivers. The Corbett Administration put an end to that practice, which means most western Pennsylvania operations are now evaporating their fluid, and then transporting the concentrated brine to Ohio, where it’s disposed into underground caverns, called deep well injection sites.

Pennsylvania has six deep injection sites, and has recently permitted the construction of two more. But that’s not enough to take all the frack water.

It’s a longer haul to the Buckeye State from north central Pennsylvania, though. So in the Williamsport area, Range and other drillers bring their fracking fluid to a private water treatment facility capable of cleaning it up. Some of the cleaned-up water is then hauled to a separate wastewater treatment plant, where it’s processed along with other industrial fluids. Some of it is used to frack more wells. But there will always be some portion of that water that contains high levels of salts and radioactive material. That “concentrate” gets shipped to Ohio, or to one of Pennsylvania’s deep wells, and is shot at high pressure back into the earth.