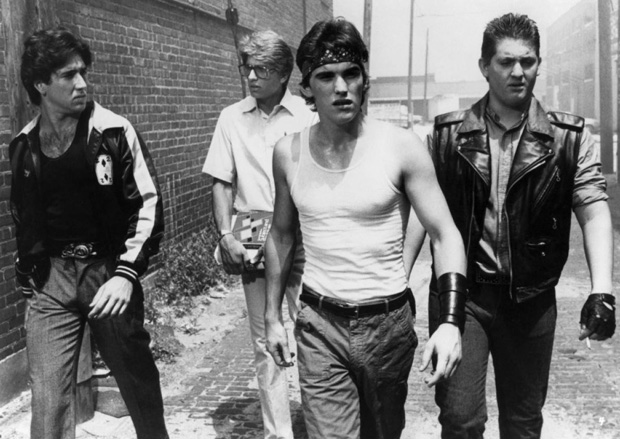

caption

Still/Universal Pictures

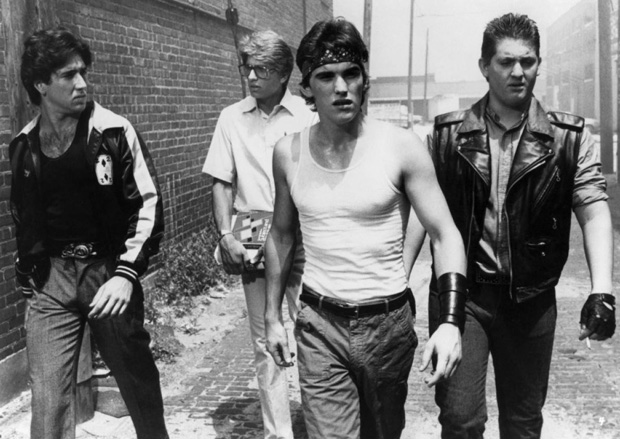

caption

Still/Universal Pictures

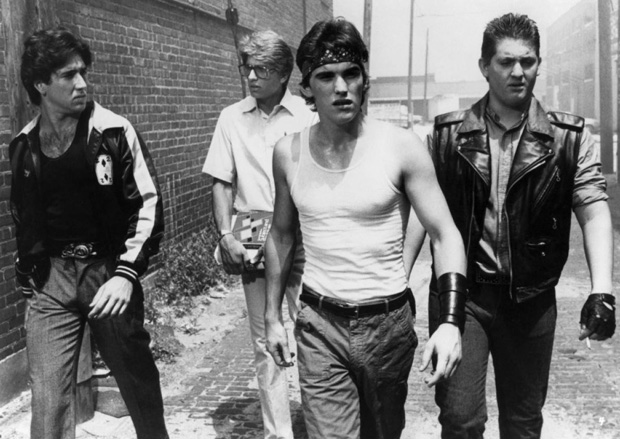

Universal Pictures

Without tax credits, cash-strapped studios today might have filmed Francis Ford Coppola's Tulsa-set Rumble Fish in another state or country, state film officials said on Wednesday.

A filmmaker, screenwriter and general contractor joined tourism officials at the state Capitol on Wednesday to defend rebates created to bring movie productions to Oklahoma.

The supporters spoke to the 10-member tax credit task force, which is examining the economic value of various tax credits and incentive programs.

Qualifying movie projects can receive a rebate of up to 37 percent of in-state expenditures. The program is capped at $5 million per year. The Oklahoma Film and Music Office, which oversees the incentive program, tried unsuccessfully to get the legislature to double the cap to $10 million this year.

Most of the dialog from Wednesday’s script went to the debate’s principal actors: Jobs and Competition.

Production companies hire Oklahomans and pay local businesses for goods and services when they film in state. The flow of money is both direct, through on-set jobs —electricians, stylists, assistants, etc. — and ancillary, through patronage of local businesses like caterers, restaurants or transportation companies.

[module align=”right” width=”half” type=”pull-quote”]

If we didn’t have incentives … they would shoot a movie about greasers in Tulsa — in Michigan.

[/module]

Like all programs under examination, the task force wanted to know if Oklahoma’s film program was creating jobs. The debate was divided into two key questions.

1. How Many New Jobs Do Film Productions Bring?

Joseph Henchman, vice president for legal and state projects with the Tax Foundation, who flew in from Washington, D.C., to speak at the meeting, said that film rebates and credits don’t create enough new jobs to offset their costs in tax revenue.

Restaurants, hair stylists and hotels, Henchman suggested, would have customers whether or not there was a film production in town.

“They may not have gotten all of the revenue, but they would have gotten some,” he said.

The Tax Foundation, a nonprofit tax research group based in D.C., has been critical of state-run film incentive programs. Competition between states to attract movie projects brings big gains to film industry, “not to local businesses or state coffers,” Henchman wrote on the foundation’s website.

Stacey Witter, a general contractor based out of Oklahoma City, also spoke at Wednesday’s meeting. He told the task force that film projects are bringing his company new work.

Stacey Witter & Associates built sets for Yellow, which was written by The Notebook director Nick Cassavetes and filmed in Pauls Valley, Seminole and McAlester. The film stars Melanie Griffith, Sienna Miller and Gena Rowlands.

2. How Many Actual Jobs Are Created?

A study by Oklahoma City University’s Economic Research & Policy Institute found that $4.6 million in direct project expenditures in FY2010 yielded an economic impact of $11.8 million, which supported 157 full-time equivalent jobs.

The jobs number is an estimation based on expenditures, and the study didn’t include a survey of jobs created directly from film productions. Using the study’s expenditure formula, the Film and Music Office estimated that the number of full-time equivalent jobs grew to 279 in 2011; and to 513 in 2012.

Joe Wertz / NPR StateImpact

Tracy Trost of Tulsa-based Trost Moving Pictures told the task force that Oklahoma's film rebate program keeps him from making movies in Michigan.

Such impact studies approximate results through economic “multipliers,” which are an inexact science, admitted OCU economist Kyle Dean, who spoke at the meeting.

The inexactness of the estimations didn’t please Rep. Mike Reynolds.

“Don’t you think it would be possible to go poll those companies and find out the exact number of jobs?,” he asked Dean, who replied by reiterating the limited parameters of the study.

“We ought to have a disclaimer that that’s just a guess based on how much money we pitched out,” Reynolds said.

The notion that states need rebates, incentives and tax credits to lure filmmakers is false, Henchman said.

But Simpson said production companies have changed the way they shop for locations.

Years ago, moviemakers prioritized geography and location, focusing on states that provided the look, setting or scene that the film required, she said.

Location is now the last thing production companies ask about, Simpson said. The first two questions, according to Simpson: “What’s your incentive program?” and “Is it funded?”

Incentives can tip the scale even when Oklahoma is intrinsically linked to a film project’s characters or setting, Simpson said.

An upcoming movie starring Oklahoma City Thunder forward Kevin Durant recently began production in Louisiana despite the fact that the team and arena play a central role in the film.

The competition isn’t just between states, Simpson said. Film office staffers worked for months this summer to scout locations for Steven Spielberg’s Robopocalypse, which is set in futuristic Oklahoma. In the end, the film was relocated to Canada because of that country’s extensive film incentive program, Simpson said.

The addition of state film incentive programs parallels Hollywood cost cutting, Simpson said. Prior to the studio cutbacks, Oklahoma attracted big-budget movies, she said, noting that the state now largely appeals to independent moviemakers spending less than $15 million.

Because of other more competitive incentive programs in other states and countries, Oklahoma today likely wouldn’t attract some of its best-known projects, including Outsiders, Rumble Fish, and Twister.

“I promise you we would not have any of that today if we didn’t have incentives,” Simpson said. “They would shoot a movie about greasers in Tulsa — in Michigan.”