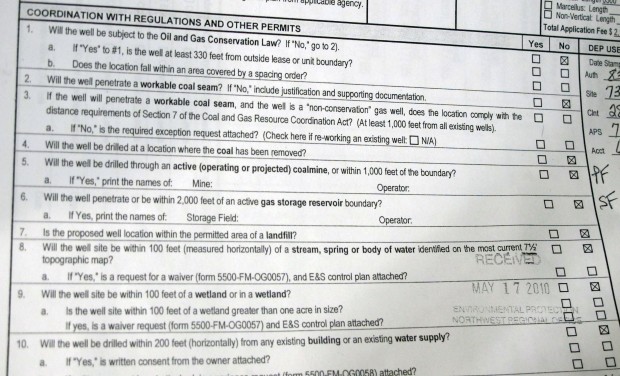

Shell subsidiary East Resources's permit application for a Marcellus Shale well in Union Township, Tioga County

Scott Detrow / StateImpact Pennsylvania

Shell subsidiary East Resources's permit application for a Marcellus Shale well in Union Township, Tioga County

Scott Detrow / StateImpact Pennsylvania

Scott Detrow / StateImpact Pennsylvania

Shell subsidiary East Resources's permit application for a Marcellus Shale well in Union Township, Tioga County

Scott Detrow / StateImpact Pennsylvania

Shell subsidiary East Resources's permit application for a Marcellus Shale well in Union Township, Tioga County

A geyser of methane and gas sprays out of the ground near a Shell drilling site in Tioga County. StateImpact Pennsylvania obtained this picture from a nearby landowner.

One of the best indications of how a state’s oil and gas drilling regulations stack up against its counterparts is a peer review process called “STRONGER.” The acronym stands for State Review of Oil and Natural Gas Environmental Regulations. STRONGER is governed by a board representing state regulators, the energy industry, and environmental groups. States voluntarily submit their drilling regulations to the board for analysis and review.

[module align=”left” width=”half” type=”aside”]

How Other States Regulate Drilling Near Abandoned Wells

Ohio: A board representing state regulators, the energy industry and environmental groups, called STRONGER, studied the Buckeye State’s application process. They noted that the process “includes a review of wells or other potential pathways for contamination of groundwater within the minimum spacing distance of the well….The review includes plugging records for plugged wells and casing records for other offset wells,” which the review team pointed out was “both appropriate and commendable.”

Texas: A spokesman for the Texas Railroad Commission, which regulates drilling in the state, says Texas doesn’t require drillers to stay a certain distance from plugged wells or actively search for them. Ramona Nye tells StateImpact Pennsylvania, “operators generally do such a survey as part of due diligence to reduce the potential of intercepting an old well and causing a blowout through an old, unplugged well.”

Texas does require injection well operators to search for unplugged, abandoned wells within a quarter mile – and at times a half-mile – from their proposed sites. Injection wells are used to dispose of fracking fluid and other liquid waste deep underground. They’ve been linked to minor earthquakes in recent years.

West Virginia: The state bars drilling within a certain distance of water wells, buildings or springs, but places no restriction on drilling near the state’s 13,000 known abandoned wells.

[/module] Pennsylvania has done this four times, most recently in 2010. And while the review team concluded Pennsylvania’s drilling oversight was “well-managed, professional and meeting its program objectives,” it took issue with Pennsylvania’s lack of regulations regarding drilling near abandoned wells.

“The review team also noted that DEP has not required operators to identify potential conduits for fluid migration,” the document reads. It urges the state to identify situations where active or abandoned wells could provide pathways for fluid to migrate to the surface, and then “require operators to identify and eliminate these potential pathways…before conducting hydraulic fracturing operations.”

The STRONGER review focused on wells’ potential to serve as a pathway for drilling fluids, not methane gas. Still, it suggested including information about the abandoned sites in permit applications.

Pennsylvania has overhauled its drilling standards twice since STRONGER returned its opinion. A set of regulations that went into effect in February 2011 requires drillers to use top-grade cement and steel casing in their wells, in order to help eliminate methane gas leaks. But the rules do not address the issue of abandoned wells, which provide a much more direct pathway for gas to reach the surface.

A year later, Governor Tom Corbett signed a law updating Pennsylvania’s Oil and Gas Act for the first time in nearly three decades. Act 13 imposed a host of substantial changes. For example, wells can’t be located within 300 feet of streams, or within 1,000 feet of “water supply extraction point[s].” The law did not follow up on STRONGER’s recommendation about drilling near abandoned wells.

The third time may be different. The Department of Environmental Protection has begun the process of once again updating its natural gas drilling regulations. The draft proposal suggests “adding a requirement that a well operator identify on the well permit application the location of abandoned gas or oil wells within 1,000 feet of the entire well bore length.”

It may take a while for the regulation to be finalized, though. Three different state panels — the Oil and Gas Technical Advisory Board, Environmental Quality Board, and Independent Regulatory Review Commission — need to weigh in on the language, and public comment must be solicited. By the time the process plays itself out, it could be early 2014.

Other parts of the Perilous Pathways series:

Part 1: Why abandoned wells are a problem

Infographic: How abandoned wells can contribute to methane migration

Part 2: How many wells dot Pennsylvania, and why aren’t we plugging more of them?

Map: Known abandoned wells in Pennsylvania

Part 3: How to track down an abandoned well

Part 4: States don’t do much to regulate drilling near abandoned wells

StateImpact Pennsylvania is a collaboration among WITF, WHYY, and the Allegheny Front. Reporters Reid Frazier, Rachel McDevitt and Susan Phillips cover the commonwealth’s energy economy. Read their reports on this site, and hear them on public radio stations across Pennsylvania.

(listed by story count)

StateImpact Pennsylvania is a collaboration among WITF, WHYY, and the Allegheny Front. Reporters Reid Frazier, Rachel McDevitt and Susan Phillips cover the commonwealth’s energy economy. Read their reports on this site, and hear them on public radio stations across Pennsylvania.

Climate Solutions, a collaboration of news organizations, educational institutions and a theater company, uses engagement, education and storytelling to help central Pennsylvanians toward climate change literacy, resilience and adaptation. Our work will amplify how people are finding solutions to the challenges presented by a warming world.