Older Pa. gas storage wells threaten methane leaks, study says

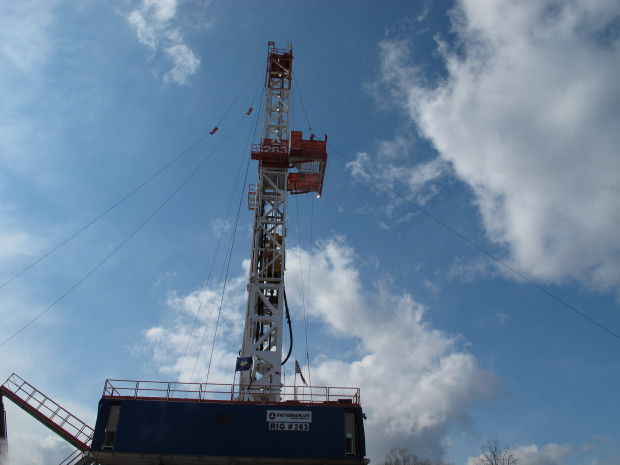

Scott Detrow / StateImpact PA

An academic study raised questions about the safety of underground storage of gas from wells like this in Dimock, Pa.

Pennsylvania has hundreds of underground natural gas storage sites that are vulnerable to methane leaks because they were built at least 60 years ago, and were probably never designed to store gas, according to a Harvard University study released on Tuesday.

The national study said Pennsylvania has 830 such sites that are in active use for gas storage, 370 of which are older wells that likely have design deficiencies such as only one casing. One hundred twenty-three of them were built more than 100 years ago.

Older wells are increasingly vulnerable to leaks as has been happening in California’s Aliso Canyon. Beginning in late 2015 leaks there forced nearby residents to leave their homes, and resulted in the biggest accidental leak of greenhouse gases in U.S. history, according to the authors of the study. They said the older storage wells in Pennsylvania and other states are likely to have been built to similar standards as in California.

Nationwide, more than one in five underground natural gas storage (UGS) sites in 19 states are vulnerable to such incidents; the oldest wells are concentrated in Pennsylvania – where the median age is 70 years – as well as Ohio, West Virginia and New York, the study said.

Using federal, state and company data, the researchers identified more than 14,000 storage wells in 29 states. Of the total, about 2,700 were never designed to hold gas, and had a median age of 74 years suggesting that many are vulnerable to the kind of leak that caused the California incident, said Dr. Drew Michanowicz of Harvard University’s Center for Health and Global Environment, which conducted the 18-month study.

The California well was first drilled for oil in 1954 and lacked the multiple levels of steel and concrete that separate fuel flows from surrounding rock in modern gas wells. As a result, it was vulnerable to the failure of a single point in its infrastructure, contributing to the 2015 leak, the study found.

Other incidents involving underground gas storage occurred in Hutchinson, Kansas in 2001 and at Moss Bluff, Texas in 2004, Michanowicz said.

“Some of these wells are over 100 years old,” he said in an interview. “There’s been a lot of focus on emerging risk but this seems to be one of the hazards that has been flying somewhat under the radar.

“This is another surprise associated with switching to natural gas,” he said. “We are building up an infrastructure to support natural gas for the foreseeable future so we needed to get a better handle on the risks associated with it.”

In Pennsylvania, the Harvard team drew on data from the Department of Environmental Protection which regulates the underground storage, and provided information such as the location and construction date of each well but not the specific construction details, Michanowicz said.

Neil Shader, a DEP spokesman, said the department is reviewing the study, but has “stringent” regulations on issues such as well casings, integrity and pressure limits at the 63 storage fields that it regulates.

At the federal level, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration issued a new rule late last year to implement the so-called PIPES Act of 2016, which required the agency to implement minimum safety standards for underground gas storage, while addressing public concerns about the Aliso Canyon leak. The rule is due to be finalized this July.

Lynda Farrell, executive director of the Pennsylvania-based Pipeline Safety Coalition, called the study a “distinguished” set of data that highlights concerns about the speed of the natural gas revolution in Pennsylvania and beyond. “This is one of the most encouraging things I have seen in a while,” she said.

Farrell said the increasing age of the storage wells points to the need for tighter regulation at state or federal levels. “There is no excuse for the lack of that kind of oversight,” she said.

Across the country, the study identified 2,715 wells that were not designed to hold gas but have been repurposed to do so. Of the total, 88 percent were in five states including Pennsylvania.

The “highest priority”, the study said, was the 210 wells that were built before 1917 in Pennsylvania and three other states.

The Interstate Natural Gas Association of America, which represents pipeline operators, rejected the study’s findings, saying there is no evidence that wells that have been reused for underground gas storage are unsafe.

“The federal storage regulations, like the gas pipeline safety regulations that preceded it, take a functional integrity approach to storage safety,” said Catherine Landry, a spokeswoman for the trade group. “These regulations complement existing state regulations and require operators to develop rigorous risk-assessment programs.”