Preparing for the worst, Delco first responders simulate oil train accident

Susan Phillips / StateImpact Pennsylvania

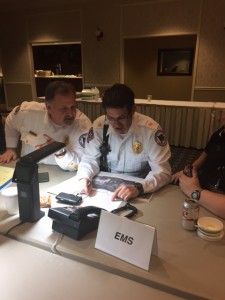

Delaware County EMS personal try to find a way to get their vehicles to the site of an oil train incident during a practice run.

The increasing number of rail cars carrying crude oil through Pennsylvania means a rising risk of accidents. Recent derailments caused trains to explode and incinerate areas along tracks in Illinois and West Virginia, threatening waterways. So far, Pennsylvania has been lucky. Within the past year and a half, oil trains traveling through the state derailed in Philadelphia, Vandergrift and McKeesport, but none of them exploded.

Back in the sumer of 2013, that wasn’t the case in the Quebec village of Lac Megantic, where an oil train crash killed 47 people. Five bodies were never recovered, having been incinerated.

Nationwide, oil train traffic has increased 4000 percent since 2008. And Philadelphia is a top destination for these trains, which haul millions of gallons of volatile crude oil from the Bakken Shale fields in North Dakota to area refineries each week. With the increase in oil train traffic from North Dakota, the Department of Transportation predicts an average of 10 of these trains will derail each year.

While activists and politicians push Philadelphia’s emergency planning operation to disclose their response plans, neighboring Delaware County has forged ahead with practice runs.

About 150 first responders, from local, state, and federal agencies gathered at the Lazaretto Ballroom in Tinicum Township Delaware County last week. The training exercise was for this new danger – crude-by-rail shipments. The room was full of uniformed first responders from some of Delaware County’s 80 separate volunteer fire companies.

A voice came over the loud speaker:

“Local 911 dispatcher fire, police, EMS and emergency managers, subject train derailment and fire. 911 dispatch continues to receive calls recording a train derailment and fire on the Conrail tracks just east of the Darby creek bridge. Fire, police and EMS units dispatched to the scene, there are no reports of injuries at this time. Approach with caution, signed, 911 Dispatch.”

Once they hear the 911 announcement the teams of firefighters, police, EMS, contractors, politicians and railroad officials, jumped into the role play. For them, this banquet hall acts as the accident scene. Voices shout over one another.

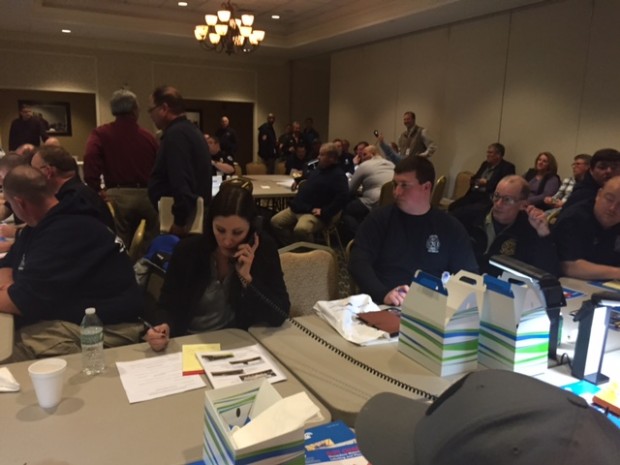

Susan Phillips / StateImpact Pennsylvania

Teams of first responders role play an emergency response to a crude by rail explosion on the Darby Creek bridge.

“We need to know what our access points are how do we get in and out.”

“OIC! OIC! I got Conrail on the scene here and they’ve given me a list of resources and time frame of resources, when you’re ready give me a call I’ll give them to you.”

“I need to know how to get in and out and I need to know how many victims.”

For this exercise, an oil train heading to one of the refineries derailed on a bridge over Darby Creek; one train car exploded. A huge plume of black smoke rose over southeastern Delaware County. An aerial picture on a large screen showed the location, not far from the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge, with the Delaware River is just a half mile downstream.

This exercise is designed to be as realistic as possible. And because it’s an emergency situation that no one here has ever encountered, chaos and confusion can reign. A disagreement cropped up over how many cars are derailed. Is it six? or 60? How long is an oil train? Where’s the front or the back?

But that’s what’s supposed to happen at these trainings.

“It really simulates what happens at a real scene,” said Ed Doyle, chairman of Delaware County’s Local Emergency Planning Committee.

“Cause you’re getting to a scene and you’ve got that flame and that smoke, and that smoke can be seen for miles around and the first thing you say to yourself is ‘oh, what am I going to do with this?”

In a separate room, meant to be off-scene, the county’s emergency planners were thinking about food, volunteers and evacuations. The exercise included members of federal agencies, who stood by. Calls got made to WaWa for food. Someone took charge of getting a trailer with phones, and computer hook-ups.

Susan Phillips / StateImpact Pennsylvania

Delaware County emergency manager Ed Truitt watches as more than 150 emergency responders role play the crude by rail accident.

Watching from a folding chair set between the two rooms was the mastermind behind this exercise. Ed Truitt has been Delaware County’s emergency manager for 30 years.

“Relationships, it’s the key to the whole thing,” says Truitt. “You have to develop relationships with the people you work with that are helping you protect your people. You can’t make a friend the day of the incident.”

Truitt says that local authorities are in charge at the scene of disasters, while the county, state and federal officials provide support. The key, he says, is that everyone knows each other, but even more importantly everyone knows the chain of command. Including officials from the EPA, FEMA, and the Coast Guard.

“We try to keep the federal guys that show up away from the action because [while] they want to do something, but they’re not quite sure what they’re supposed to do,” he said. “So what they wind up doing is not always the right thing to do. Oh. Let’s see what it says on page 3 of the book, you know, that kind of stuff.”

Truitt said there’s no book of instructions for any emergency. He said there are times when it makes sense to put out the fire. But other times when it makes sense to let it burn, especially if there’s a risk of oil leaking into a waterway and contaminating watersheds downstream.

“The Coast Guard may say, we’re controlling this, there’s nothing dangerous in the smoke, let it burn,” said Truitt. “That may be the most practical solution. Now, to the people in the media, they may say there’s something wrong with that. No there isn’t. We’re doing the best thing for the environment as well as to mitigate the emergency.”

Truitt began working on a crude by rail emergency response plan several years ago even before the oil trains started heading to the refineries. He pointed to his friend Jack Galloway, an executive at Eddystone Rail Company. Truitt said once he heard about the plan to bring in crude by rail, he got Galloway to help create an emergency response.

“And we did that with a handshake and he kept his word,” said Truitt. “That’s a guy I’ve known for 40 odd years.”

His friend Jack Galloway says there was no hesitation.

“Why did I agree to that? It’s only good citizenship.”

Galloway says it’s highly unlikely that these trains would derail in Delaware County because they move through this industrial and highly populated area at a snails pace, just 10 to 15 miles an hour. That’s a lot slower than the rate at which most oil trains move. In fact, newly proposed federal regulations would limit the trains to 40 miles an hour in urban areas.

Delaware County is home to about 26 different industrial facilities that handle hazardous material. But crude-by-rail is the most recent addition. In this practice run, 500 people were within the evacuation zone. The plan was to open up a shelter at Interboro High School.

John McBlain is a Delaware County Councilman and attended the exercise.

“There has been a lot of discussion about the transportation of crude oil, and a lot of the discussion centers around the benefits to the economy of Delaware County,” McBlain said. “But also the caveat along with that every time is as much as we want those economic benefits and we want the thousands of jobs that it will bring the most important duty that we have is for public safety.”

This won’t be the last oil train exercise. Delaware County’s emergency manager Ed Truitt says whatever they learn from this will be incorporated in their emergency plan, and they’ll do the whole thing over next year.

“The key is that the more informed the local emergency response community and public officials are, the better informed the public is.”

Responding to recent oil train explosions both in the U.S. and Canada, the federal agency plans to issue new rules for carrying crude by rail in May.