How Purdue Aims To Boost One Of The Big Ten's Lowest Graduation Rates

Kyle Stokes / StateImpact Indiana

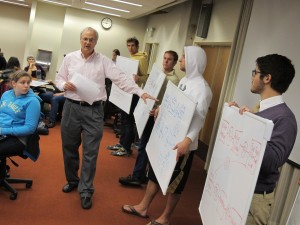

Prof. Larry Nies leads a discussion in his environmental engineering course. This year, Nies redesigned the class's structure to make it more student-driven and discussion-based.

Purdue’s newest lecture hall isn’t really a “lecture” hall at all.

Instead of rows of auditorium seating, moveable circular tables and chairs fill the cavernous room in an underground library — a space West Lafayette administrators hope will get more students engaged and on-track.

Saddled with one of the lowest four-year graduation rates in the Big Ten, Purdue redesigned 10 first- and second-year courses — all formerly taught in a traditional lecture format — to be more interactive and student-driven.

Administrators hope revamping these courses will stop freshmen from falling behind and help the university earn a bigger share of $61 million in performance funding from the state.

- Purdue's Big Lecture OverhaulStateImpact Indiana‘s Kyle Stokes visits Purdue’s West Lafayette campus, where instructors hope they can retool several large lecture courses to be more engaging for first- and second-year students.Download

| Four-Year Graduation Rates, Big Ten Schools (2008) | |

|---|---|

| Northwestern | 86% |

| Michigan – Ann Arbor | 72% |

| Illinois – Urbana/Champaign | 67% |

| Penn State | 62% |

| Indiana – Bloomington | 50% |

| Wisconsin – Madison | 50% |

| Ohio State | 49% |

| Michigan State | 48% |

| Minnesota – Twin Cities | 46% |

| Iowa | 44% |

| Purdue – West Lafayette | 38%* |

| Nebraska – Lincoln | 29% |

SOURCE: NCES, 2008 data

|

|

“Our state legislators, our parents, they don’t want the students dropping out,” says Marne Helgesen, director of Purdue’s Center for Instructional Excellence, which is overseeing the school’s course redesign, called the “IMPACT” program.

Nearly 3,000 Purdue students have signed up for courses revamped to emphasize active teaching methods, from “Elementary Psychology” to “Basic Mechanics II.”

Some courses involve interactive discussion groups, others require watching lecture videos online outside of class or the use of new technologies in class.

But Purdue administrators and teachers intend all courses in the IMPACT program to challenge the expectation that college students learn in settings where information is presented to them passively — what Purdue professor Larry Nies terms “filing facts into your brain.”

“What we’re supposed to be teaching students is how to take those facts and assemble them and synthesize them and do something with them,” says Nies, who redesigned his environmental engineering course by imitating the principles used in the IMPACT program.

It’s too early to know whether the program is actually affecting on student performance. Nies says his class’s grades ride largely on the cumulative final exam, which isn’t taken until mid-December.

If students’ grades and graduation rates do change, it’s possible the program could have a direct effect on Purdue’s state funding.

In the 2011-2013 budget, Purdue-West Lafayette grabbed a $14.7 million share of a total of $122.1 million in performance funding, which the state distributed to all Indiana public universities based on their levels on-time graduation, success rates for low-income students, and other similar metrics.

Indiana higher education commissioner Teresa Lubbers says Purdue’s effort to redesign its courses fits the state’s overall vision of a more “student-centric” university system. In a similar vein, Lubbers says the state’s two-year colleges are looking at revamping remediation courses to be more engaging for students.

“As we’re serving a larger portion of the population going to college, we need to make sure that students aren’t only going to college — often borrowing money to do so — but that they’re exiting college with a credential that benefits them,” Lubbers says.

Purdue senior Nadim Chakroun, who’s in Nies’s environmental engineering class, says most of his classes in college have been in traditional lecture formats. He says a discussion-based model works better for this type of class.

“If you just work on your own, it’s hard to come up with ideas. If you have a group, you can bounce ideas of different people to get their input, because we’re all different types of engineers,” Chakroun says.

The adjustment to the new model hasn’t come without challenges for students and teachers. Nies says it was easy for him to lecture for 50 minutes, answer a few questions, and call it a day. Nies says he was “utterly miserable” in this setting, but he also says student evaluations show they still prefer this method.

“They’re still of the mindset that they would really prefer that I just tell them all the right answers, in a lecture format — very much them being passive and me being active,” he says.

But in the end, Nies says the old way isn’t effective.

“If I just tell them what the answer is, probably 70 percent of [students] will forget it an hour later, 90 percent by 5 o’clock that evening, and only 3 of them will remember it,” Nies says. “Then, if they were going to take a test, they would all relearn it again, and forget it after the test. But if you make them fight through it and discover the answer, they’re gonna remember it.”

CORRECTION: In a previous incarnation of the above table, the author committed one of his own pet peeves by confusing the graduation rates of the University of Michigan and Michigan State University. He hates it when people do that with “State” universities. Unlike Victoria’s Secret designers, he knows the difference between the Spartans and Wolverines and regrets the error, which he chalks up to one missed cell in Excel. Hail To The Victors! and Sparty On!, respectively.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download